Art of ASEAN: Our Exhibition @ Sasana Kijang

“…ASEAN’s fundamental and enduring purpose is to ensure a modicum of order and civility in a region where neither is to be taken for granted […] ASEAN works by consensus and can only work by consensus. This is because Southeast Asia is a very diverse region and ASEAN member states differ in levels of economic development; we differ in types of political systems; we differ in our core identities of race, language and religion; and hence we often differ in how each of us defines our national interests within the ASEAN framework even though we all have come to accept that framework as one of our most important shared interests.”

- Singapore diplomat Bilahari Kausikan, ‘A Cow is Not A Horse’, opening speech at the Youth Model ASEAN Conference, 5th Oct 2015

|

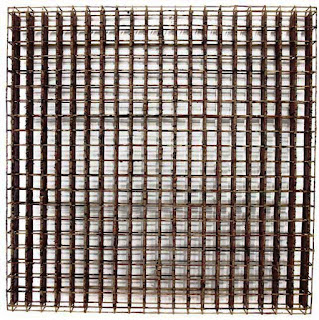

| Sopheap Pich - Untitled (Red Square Wall Relief) (2015) |

No cows or horses are referenced in the three sections of this group exhibition, titled “Bridging Past and Present”, “Between Us, Among Us”, and “Formation and Linkages” respectively. These ambiguous statements are synonymous and fitting descriptions, of the non-interference protocol observed by members in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Collaboration, people, and community, are further touted as keywords. Displayed beside the ASEAN emblem is Multhalib Musa’s ‘Squeezing Tightly’, a wonderful bent sculpture that illustrates unity as recounted in Aesop’s Fable ‘The Bundle of Sticks’. Multhalib also collaborated with Hamir Soib for ‘Landlord vs Raja Tanah’, a giant depressed countenance constructed from jigsaw-shaped mild steel pieces. Why so serious?

| [front] Hamir Soib (collaboration with Multhalib Musa) - Landlord vs Raja Tanah (2009); [back] Trinnapat Chaisittisak - Dynamic (2010) |

A visual puzzle describes two works by Chang Yoong Chia – the first an oil painting featuring household objects embedded within its monochromatic landscape, the second an ambitious world map made from stamps recounting contemporary issues. Other works with literal statements are contributed by Indonesian artists – who are poorly represented here – which call into question how this exhibition is put together. Its acknowledgement list includes notable galleries and regional collectors, yet it is clear that the responsibility to gather artworks has been delegated to separate individuals. One can imagine such a conversation taking place – “…who’s got works by Filipino and Vietnamese artists? You do? Great! Whoever also can…”

| Close-ups of works by Chang Yoong Chia - [top] Ten Things I Love About You (2009); [bottom] The World is Flat (2010) |

Black paintings and a tall bicycle are contributed by Singaporean artists, a good indication of the type of art produced in the island state. Walking past and rolling my eyes at a royal quote, two Bruneian works surprise with its elegant forms. Zakaria Omar’s ‘Unbalances Series Tsunami’ paints a golden batik portrait on corrugated zinc, while the more senior Hj Mahaddi Hj Mat Zain utilises thick lines in a serene drawing about religious devotion. Cambodian Sopheap Pich presents a brownish-red grid made from natural materials, its raw texture sufficiently drawing one in to look closer. Commissioned for the Singapore Biennale 2013, Lao Marisa Darasavath’s large colourful painting loses potency in this gallery, where many depictions of toiling farmers have been exhibited.

| Zakaria Omar - Unbalances Series Tsunami (2013) |

It is telling that works by female artists are more visually captivating and nuanced in content, as compared to male peers. From Nadiah Bamadhaj’s striking paper creations, to the nostalgic photo-collages of Nge Lay, to a patterned wooden construct by Anniketyni Madian – personal intention and crafted output maintain a wonderful balance. Six photographs from Anida Yoeu Ali’s “The Buddhist Bug Project” are easily the highlight of this exhibition. Anida dons a saffron-coloured hijab with a long tail then interacts with people at public places. Wide-eyed onlookers are captured in outlandish pictures, yet the religious references remain potent especially in a classroom setting, or when the artist occupies one table at a university cafeteria by herself.

|

| Anida Yoeu Ali - Campus Dining (2012) |

In the gallery opposite, stunning line drawings by Thai artists Imhathai Suwatthanasilp and Jiratchaya Pripwai captivate endlessly, although I harboured hope to see the former’s renowned hair sculptures. Despite the wide diversity on show, minimal narratives are weaved, which aptly alludes to the large cultural and economic differences between ASEAN countries. As the exhibition introduction states, “(d)espite the physical proximity of these ASEAN countries, it is rare to find works from all 10 nations assembled in one place.” As such, Haslin Ismail’s painting of guts laid out on a large canvas proves to be the most subversive expression on display. We are polite to each other now, but in the past, we once battled each other to death.

| Haslin Ismail - The Pattern of Chaos (2014) |

“The influence and inspiration came after giving birth to my first child. We had this collapsible play tunnel that really intrigued me structurally. What it was able to do was expand into this tunnel in which my daughter could climb into and have loads of fun, and then it could easily collapse and be put away. That structure really appealed to me. As I looked at it for a long time, I started to sketch things in my notebook that ultimately became the Bug. That idea of creating a soft sculpture from an expansive fabric that could easily fold up and be carried on my back is a direct reference to the refugee experience and the fact that we left our countries and arrived at the camps with nothing but the clothes on our backs.”

- Anida Yoeu Ali, interview with Art Radar, published on 19th Mar 2013 [posted at artradarjournal.com]

| Imhathai Suwatthanasilp - Leave Leaf No. 1 (2014); Reflected in the background is Hafiz Osman - The Penghulu (2015) |

Comments

Post a Comment